From Taylor Swift to the Royal Family – deepfakes are rarely out of the news. BDFI’s Prof. Colin Gavaghan asks what we can do to protect ourselves and if lawmakers should be doing more.

The camera does lie. It always has. For as long as we’ve had photography, we’ve had trick photography. Some of this is harmless fun. I remember as a child delighting in forced perspective photos that made it look like I was holding a tiny building or relative in the palm of my hand. Some of it is much less than harmless. Stalin was notorious for doctoring old photographs to excise those who had fallen from his favour.

The development of AI deepfakes has taken this to a new level. It’s not just static images that can be manipulated now. People can be depicted saying and doing things that are entirely invented.

If anyone hadn’t heard of deepfakes before, the first few months of 2024 have surely remedied that. First, in January, deepfake sexual images of Taylor Swift – probably the world’s most famous pop star – were circulated on X and 4chan. This month, deepfakes were back among the headlines, when rumours circulated that a family picture by the Princess of Wales had been digitally altered by AI.

In some ways, the stories couldn’t be more different. The Taylor Swift images were made and circulated by unknown actors, without the subject’s consent, and in a manner surely known or intended to cause embarrassment and distress.

Princess Kate’s picture, in contrast – which it turns out was more likely edited by more basic software like Photoshop – was made and shared by the subject herself, and any embarrassment will be trivial and to do with her amateur photo editing skills.

In other ways, though, the two stories show two sides of the challenge these technologies will pose.

The challenges posed by intimate deepfakes are the more obvious, and have been known about long before Taylor Swift became their most high profile victim. As with ‘revenge porn”, the victims are overwhelmingly women and girls, and the harm it can do is well documented.

There have been legal responses to this. The new Online Safety Act introduced a series of criminal offences aimed at the intentional sharing of “a photograph or film which shows, or appears to show, another person in an intimate state” without their consent. The wording is specifically intended to capture AI generated or altered images. These offences are not messing around either. The most serious of them carries a maximum prison sentence of two years.

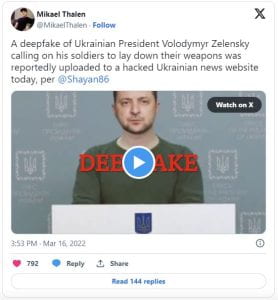

That sort of regulatory response targets the users of deepfake technologies. Though it’s hoped they have some deterrent effect, they are retrospective responses, handing out punishment after the harm is done. They also don’t have anything to say about a potentially even more pernicious use of deepfakes; the generation of fake political content. In 2022 a fake video circulated of Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky appearing to announce the country’s surrender to Russia. And in January this year, voters in new Hampshire received a phone call from a deepfake “Joe Biden”, telling them not to vote in the Democrat primary.

Unlike intimate deepfakes, political deepfakes don’t always have an obvious individual victim. The harms are likely to be more collective – to the democratic process, perhaps, or national security. It would be possible to create specific offences to cover these situations too. Indeed, the US Federal Communications Commission acted promptly after the Biden deepfake to do precisely that.

An alternative response, though, would be to target the technologies themselves. The EU has gone some way in this direction. Article 52 of the forthcoming AI Act requires that AI systems that generate synthetic content must be developed and used in such a way that their outputs are detectable as artificially generated or manipulated. The Act doesn’t specify how this would be done, but suggestions have included some sort of indelible watermark.

Will these responses help? It’s likely that the new offences will deter some people, but as with previous attempts to regulate the internet, problems are likely to exist with identification – you can’t punish someone for creating such images if you can’t find out who they are – and with jurisdiction.

What about the labelling requirements? There are technical doubts about how easy it will be to circumvent the detection system. And even when content is labelled as fake, it’s uncertain how this will affect the viewer. Early research suggests we should be cautious about assuming warnings will insulate us against fakery, with some researchers pointing out a tendency to overlook or filter out the warning: “Even when they’re there, audience members’ eyes—now trained on rapid-fire visual input—seem to unsee watermarks and disclosures.”

As for intimate deepfakes, detection systems may help a bit. But I’m struck by how the harm to these women and girls seems to persist, even when the images are exposed as fakes. In a case in Spain last year, teenaged girls had deepfake nudes created and circulated by teenaged boys. As one of the girls’ mothers told the media, “They felt bad and were afraid to tell and be blamed for it.” This internalisation of blame and shame by the victims of these actions suggests that a deeper problem may lie in persistent and damaging attitudes towards female bodies and sexuality, rather than any particular technology.

Maybe in a better future, intimate deepfakes won’t cause that level of harm. We might hope that schoolmates and neighbours will rally round the victims, and that any stigma will be reserved for the bullies and predators who have created the images. We can hope. But meanwhile, these technologies are being used to inflict considerable suffering. One solution that is gaining support would be to ban deepfake technologies altogether. Maybe the potential for harm just outweighs any potential benefit. That was certainly the view of my IT Law class last week!

But what precisely would be subject to the ban? That question brings me back to Kate’s family pic. If we are to ban “deepfakes”, where would we draw the line? Does image manipulation immediately become pernicious when AI is involved, but remain innocent when it’s done with established techniques like Photoshop? If lawmakers are going to go after the technology, rather than the use, then we’re going to have to think about precisely what technology we have in our sights.