With the persistent rise in chatbots and other human-like AI, Prof. Colin Gavaghan, BDFI’s resident tech lawyer, asks: do we need regulatory protection from manipulation?

Robots and AI that look and act like humans is a standard trope in science fiction. Recent films and tv series have supplemented the shelves of books taking this conceit as a central concept. One of the most celebrated – at least in its first season – was HBO’s reimagining of Michael Crichton’s 1973 film WestWorld.

Robots and AI that look and act like humans is a standard trope in science fiction. Recent films and tv series have supplemented the shelves of books taking this conceit as a central concept. One of the most celebrated – at least in its first season – was HBO’s reimagining of Michael Crichton’s 1973 film WestWorld.

The premise of WestWorld is well known. In a futuristic theme park, human guests can pay exorbitant sums to interact with highly realistic robots or ‘hosts’. In an early episode, a human guest, William, is greeted by Angela, a “host.” When William enquires as to whether she is “real” or a robot, Angela responds: ‘Well if you can’t tell, does it matter?’

As we move through an era where AI and robotics acquires ever greater realism in its representations of humanity, this question is acquiring increasing salience. If we can’t tell, does it matter? Evidently, quite a lot of people think it matters quite a lot. For instance, take a look at this recent blog post from the excellent Andres Gaudamuz (Technollama).

But why might it matter? In what contexts? And what, if anything, should the law have to say about it?

What’s the worry about humanlike AI?

Writing in The Atlantic a few months ago, philosopher Dan Dennett wrote this:

“Today, for the first time in history, thanks to artificial intelligence, it is possible for anybody to make counterfeit people who can pass for real in many of the new digital environments we have created. These counterfeit people are the most dangerous artifacts in human history, capable of destroying not just economies but human freedom itself.”

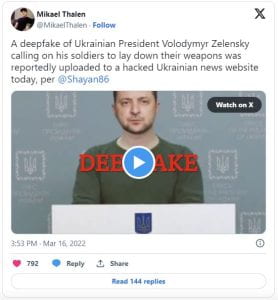

The most dangerous artifacts in human history?! In a year when the Oppenheimer film – to say nothing of events in Ukraine – have turned our attention back to the dangers of nuclear war, that is quite a claim! If we are to make sense of Dennett’s claim, far less decide whether we agree with it, we need to understand what Dennett means by “counterfeit people”. The term could refer to a number of things.

One obvious way in which AI can impersonate humans is through applications like ChatGPT, that can generate text indistinguishable from that generated by humans. When this is linked to a real-time conversational agent – a chatbot or an AI assistant – it can result in a conversation in which the human participant might reasonably believe the other party is also a human. Google’s “Duplex” personal assistant added a realistic spoken dimension to this in 2018, its naturalistic “ums” and “ahs” giving the impression of speaking to a real PA.

More recently, the Financial Times reported that Meta intends to release a range of AI “persona” chatbots, including one that talks like Abraham Lincoln, to keep users engaged with Facebook. Presumably, users will be aware that these are chatbots (does anyone think Abe Lincoln is actually on Facebook?) In other cases, the true identities of the chatbots will be concealed, as when bot accounts are used to spread propaganda and disinformation.

Those examples read and sound like they might be human. But AI can go further. Earlier this year, Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-CT) kicked off a Senate panel hearing with a fake recording of his own voice, in which he described the potential risks of AI technology. So as well as impersonating humans, we now have to be alert for AI impersonating particular humans.

As the technology evolves, we’ll find AI that can impersonate humans across a whole range of measures – not only reading and sounding human, but looking and acting like it too. This is the sort of work being done by Soul Machines, whose mission is to use “cutting edge AI technology … to create the world’s most alive Digital People.”

As the technology evolves, we’ll find AI that can impersonate humans across a whole range of measures – not only reading and sounding human, but looking and acting like it too. This is the sort of work being done by Soul Machines, whose mission is to use “cutting edge AI technology … to create the world’s most alive Digital People.”

Other than a vague unease caused by these uncanny valley denizens, why should this bother us?

One of the main concerns relates to manipulation. Writing in The Economist in April, Yuval Noah Harari claimed that AI has “hacked the operating system of human civilisation”. His concern was with the capacity of AI agents to form faux intimate relationships, and thereby exert influence on us to buy or vote in particular ways.

This concern is far from fanciful. Research is already emerging, suggesting that we are, if anything, more likely to trust AI-generated faces. Imagine an AI sales bot that is optimized to look trustworthy, and combine that with software that lets it appear patient and friendly, but also able to read our voices and faces so it knows exactly when to push and when to back off.

So great are these concerns that we have already seen some legal responses. In 2018, California introduced the BOT (Bolstering Online Transparency) Act, which bans the use of pretend-human bots if they’re used to try to influence purchasing or voting decisions. Art 52 of the EU’s new AI Act adopts a similar measure to the Californian one.

Are mandatory disclosure laws the answer?

AI agents are certainly being optimized to pass for human, with a view to sell, persuade, seduce and nudge us into parting with our attention, our money, our data, our votes. What’s less obvious is how much mandatory disclosure will insulate us against that. Will knowing that we’re interacting with an AI protect us against its superhuman persuasive power?

There is some reason to think it might play a role. One study from 2019 found that potential customers receiving a cold call about a loan renewal offer were as or more likely to take up the offer when it was made by an AI. But this advantage largely dissipated when they were told in advance that the call was from a chatbot.

Interestingly, the authors of the 2019 paper reported that late disclosure of the chatbot’s identity – that is, after the offer has been explained, but before the customer makes up their mind about whether to accept it – seemed to cancel out the antipathy to chatbots. This leads them to the provisional conclusion that experience of talking to chatbot will allay some of their concerns about it. In other words, as we get more used to talking with AIs, our intuitive suspicion of them will likely dissipate.

Another reason to be somewhat sceptical of mandatory disclosure solutions is that telling me whether something was generated by AI tells me little or nothing about whether it’s true, or about whether the person I’m talking to is who they claim to be. Ultimately, I don’t really care if content comes from a bot, a human scammer, a Putin propaganda troll farm, or a genuine conspiracy theorist. Is “Patrick Doan”, the “author” of the email I received recently, a person or a bot? Who cares. He/it is clearly phishing me either way:

So much for cognitive misrepresentation. What about emotional manipulation? Will knowing that I’m talking to an AI help us resist the sort of emotional investment that will help the AI lead me into bad decisions?

My answer for now is: I just don’t know. What I do know, from many hours of personal experience, is that I am by no means immune to emotional investment even in the very weak AI we have now. They don’t even need to look remotely human. I’m even a sucker for the blatant emotional nudges from the little green owl if I don’t do my DuoLingo practice!

Vulnerable and lonely people are going to be even easier prey. Phishing and catfishing are likely still to be problems, whether the fisher is a human or an AI. Imagine trying to resist that AI Abraham Lincoln (or Taylor Swift or Ryan Gosling), when it’s been optimized to hit all the right sweet-talking notes.

Targeted steps forward

If this all sounds like a counsel of despair, it isn’t meant to. I think there are meaningful steps that can be taken to mitigate the manipulative threat posed by human-like AI. But I suspect those measures will likely have to be properly targeted if they’re to have that effect. Simply telling me that I’m talking to a “counterfeit person” is unlikely to be enough to protect me from its persuasive superpowers.

We could, for instance, consider seriously the prospect of going hard after this sort of technology, or the worst examples of it anyway. Under the EU AI Act, those AI systems which are deemed to present an unacceptable risk are to be banned outright. This includes AI that deploys subliminal techniques beyond a person’s consciousness in order to materially distort a person’s behaviour in a manner that causes or is likely to cause that person or another person physical or psychological harm.

Perhaps there will soon be a case for adding highly persuasive AI systems to that list.

The UK Government seems to be going in a very different direction with regard to AI regulation, and the protections of the AI Act are unlikely to apply here. But other options exist. We could, for instance, consider stronger consumer law protections against manipulative AI technologies, to match those we have for “deceptive” and “aggressive” sales techniques.

In truth, I don’t have a clear idea right now about the best regulatory strategy. But it’s a subject I’m planning to look into more closely. Maybe it does matter if we can tell AI from human – at least to some people, at least some of the time. But on its own, I fear that knowledge will be nowhere near enough to prevent ever smarter AI, to use Harari’s words, hacking our operating systems.

This content is based on a paper given at the Gikii 2023 Conference in Utrecht, and at this year’s annual guest lecture at Southampton Law School. Colin is grateful for the helpful comments received at both.

Robots and AI that look and act like humans is

Robots and AI that look and act like humans is  As the technology evolves, we’ll find AI that can impersonate humans across a whole range of measures – not only reading and sounding human, but looking and acting like it too. This is the sort of work being done by

As the technology evolves, we’ll find AI that can impersonate humans across a whole range of measures – not only reading and sounding human, but looking and acting like it too. This is the sort of work being done by

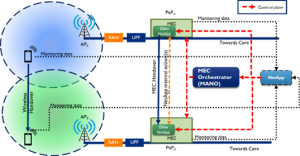

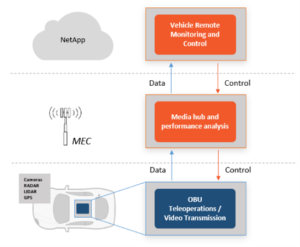

The functioning of this network application depends on collaborative machine learning (ML) predictions to maintain and potentially improve the quality of service provided by enhanced network applications operating on a multi-access edge computing (MEC) platform. The existing prototype utilizes mobile radio resource control (RRC) monitoring data along with an additional ML layer consisting of cooperative models that predict MEC handovers.

The functioning of this network application depends on collaborative machine learning (ML) predictions to maintain and potentially improve the quality of service provided by enhanced network applications operating on a multi-access edge computing (MEC) platform. The existing prototype utilizes mobile radio resource control (RRC) monitoring data along with an additional ML layer consisting of cooperative models that predict MEC handovers. This network application deploys a digital twin (DT) of a car on-board unit (OBU) on the nearest MEC node of its location. The DT can be “migrated” to car’s nearest edge as a twin (virtual) vOBU acting as a proxy, and its migration automatically begins upon cars’ movement. To avoid bottlenecks, this network application can pose an intent for forecasting future car locations with EMHO’s mobility prediction ML, thus allowing it to proactively deploy vOBU.

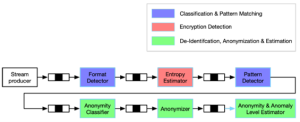

This network application deploys a digital twin (DT) of a car on-board unit (OBU) on the nearest MEC node of its location. The DT can be “migrated” to car’s nearest edge as a twin (virtual) vOBU acting as a proxy, and its migration automatically begins upon cars’ movement. To avoid bottlenecks, this network application can pose an intent for forecasting future car locations with EMHO’s mobility prediction ML, thus allowing it to proactively deploy vOBU. PrivacyAnalyser is a cross-vertical cloud-native application running either at network Core or MEC. Among other features, it caters for ML network data classification from UE and/or IoT devices, and privacy evaluation and analysis. Also, PrivacyAnalyser is converging toward ML-based network management and orchestration via EMHO’s exposed ML predictions, enabling smart scale-in/out MEC pods proactively, better than the default container autoscaling for improving energy efficiency.

PrivacyAnalyser is a cross-vertical cloud-native application running either at network Core or MEC. Among other features, it caters for ML network data classification from UE and/or IoT devices, and privacy evaluation and analysis. Also, PrivacyAnalyser is converging toward ML-based network management and orchestration via EMHO’s exposed ML predictions, enabling smart scale-in/out MEC pods proactively, better than the default container autoscaling for improving energy efficiency. This Network Application enables remote autonomous vehicle operation in unusual/dangerous situations. The intent is to ensure reliable, low-latency, high-quality real-time video transmission via AI-optimised network latency, but also via EMHO Network Application handover predictions to automatically deploy appropriate applications with optimised slice features matching dynamic needs.

This Network Application enables remote autonomous vehicle operation in unusual/dangerous situations. The intent is to ensure reliable, low-latency, high-quality real-time video transmission via AI-optimised network latency, but also via EMHO Network Application handover predictions to automatically deploy appropriate applications with optimised slice features matching dynamic needs.

Alongside our two livestream experiments, we left postcards around the festival for people to send to friends and family via a ‘post box’ in the cafe. On the back of the postcards was a link to a YouTube playlist of acts playing at the festival. Surprisingly, this activity went down particularly well with children and has a lot of scope for further experimentation such as adding art, or posting to (consenting!) strangers, or posting back and forth between people. It can also be less intense for staff to run and eliminates the stress of technology failures. After the festival we sent out craft packs to some people with links to online content – again demonstrating that to access a festival experience it doesn’t all have to synchronise or be live.

Alongside our two livestream experiments, we left postcards around the festival for people to send to friends and family via a ‘post box’ in the cafe. On the back of the postcards was a link to a YouTube playlist of acts playing at the festival. Surprisingly, this activity went down particularly well with children and has a lot of scope for further experimentation such as adding art, or posting to (consenting!) strangers, or posting back and forth between people. It can also be less intense for staff to run and eliminates the stress of technology failures. After the festival we sent out craft packs to some people with links to online content – again demonstrating that to access a festival experience it doesn’t all have to synchronise or be live.