Lena Ferriday is co-author of ‘Avon Street Gasworks and Bristol’s Gas Industry‘ with Dr James Watts, a report commissioned for BDFI to examine the histories of their renovated industrial building in St Philips, Bristol. Here she looks at the senses most provoked by the production and distribution of gas – sight and smell.

In 1861, the Bristol Mirror proclaimed that,

Of all the social improvements that the last 50 years have seen brought about, none is more significant of progress than the lighting with gas all the thoroughfares of our towns. To look back to the year 1800 in this respect and conceive what the streets […] of our own city […] were after dark, without the aid of gaslight, is a task most of us would rather shirk than encounter. Yet there are those living and walking in our midst […] who can very easily go back in memory to the period when a light was shed upon the darkness that prevailed by Winsor illuminating the metropolis.[1]

For historians of nineteenth century dark and light, the introduction of gaslighting was a revelation for urban life, stimulating a new economy where the hours of factory work and public leisure time were able to extend into the evening without the sun’s aid.[3] For Constance Classen, this innovation ‘blurred the age-old sensory divide between the visuality of daytime and the tactility of night-time’.[4] In the streets, this was indeed true. Yet as this short piece will show, in the industrial setting and on the level of company organisation, it was the interaction of sight with another sense, that of smell, that proved most important.

The first gas works was established in London in 1814. By 1819 gas works were in operation throughout the country, and in the mid-1820s most big cities were supplied with gas. The Bristol Gas Light Company first manifested in 1815 and was incorporated in 1818, working to produce coal-gas for the purposes of lighting. The first gas lamps were lit in the city, inside the Exchange, and on Wine and St. Nicholas Streets. Looking back, Bristol’s press proclaimed that from the Gas Light Company’s formation ‘we have had light shed upon our doings when the orb of day has sunk beneath the horizon, which, though it may not equal that furnished by the sun […] is yet the best substitute that has ever been discovered.’[2]

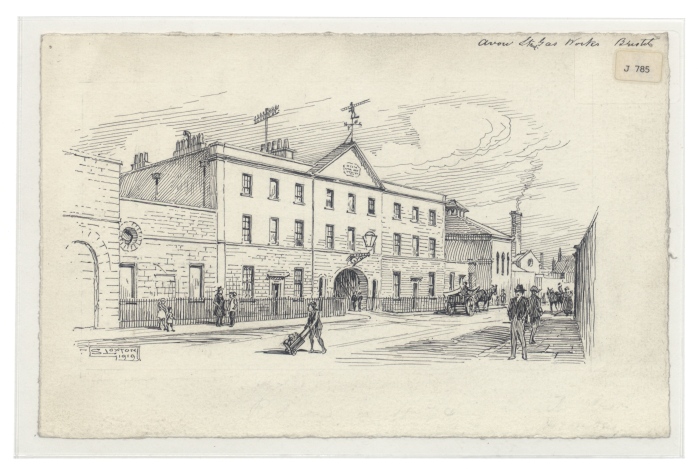

In 1821, the company headquarters expanded beyond its site at Temple Back and was rehoused to 65 Avon Street, in the building now known as ‘The Sheds’. Coal-gas was produced through a burning of coal to distil it into coke and capturing the gas that this produced, and the ‘Sheds’ was comprised of the Coal Shed, for storage, and Retort House, which the oven heating the coal to release gas, as seen in Fig. 2.

This production of gas did, however, have notoriously sensory consequences. This was not least in the noxious odours that were emitted from coal-gas as a result of its containing Hydrogen sulphide, characterised by a distinctively sulphuric scent. Despite commenting in 1861 that ‘These lights are clear, white, and beautiful – luminous, without any smoke or obnoxous effluvium, producing an effect equal to daylight, at about one-third the expense usually employed to obtain a miserable substitute’, John Breillat, one of the Gas Company’s original engineers, worked with his team across the 1820s in an attempt to reduce the smell of the gas production, and its pollution of the local area.[5] Local inhabitants also complained of the smell and in its early years calls were made for the Company to switch to the use of oil gas. extracted from whale or seal blubber.

These attempts failed, however, as the company’s management committee decided that to produce ‘the same quantity of light’ oil gas was significantly more expensive than coal, at a ratio of roughly 5:3.[6] To some extent then, sight was prioritised above smell: the importance of a gas emitting strong light to combat the darkness more important than the strength of its odour. Yet as part of their ‘exposition’ of the oil gas scheme, Bristol Mirror also concluded that ‘the ridiculous assertion of Oil-Gas being without smell, is also without foundation’, having found evidence that oil gas too ‘invaded’ homes with ‘a most distressing stench’.[7]

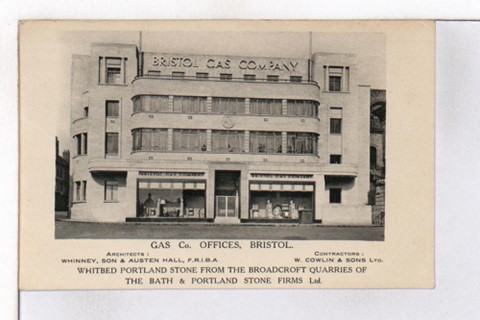

The failure to institute changes within the Gas Light Company led to a movement that formed a separate oil gas company, which by August 1823 had instated the Bristol and Clifton Oil Gas Company Act forbidding the company from using coal gas. Yet as the cost of whale oil rose in the 1830s, price differentiation once again took precedent over olfactory adversity, and the Oil Gas Company also began to use coal gas in 1836. For nearly two decades the companies operated alongside one another, each serving different Bristolian districts, until they were finally amalgamated in 1853 as the Bristol United Gaslight Company.

Whilst the changes to visual experience have commonly been seen as the key indicator of gaslight innovation’s sensory influence on urban space, in the case of Bristol’s Gasworks’ civic and industrial position the eye was not entirely dominant. For the city’s inhabitants, the gasworks were a strong-smelling presence and this sensory characteristic had great impact on the Gas Company’s bureaucratic and manufacturing development in its early years.

[1] ‘Jubilee of Gas Lighting in Bristol’, Bristol Mercury, 7 Sept 1861, p.4.

[2] ‘Jubilee of Gas Lighting in Bristol’, Bristol Mercury, 7 Sept 1861, p.4.

[3] Wolfgang Schivelbusch, Disenchanted Night: The Industrialization of Light in the Nineteenth Century, trans. Angela Davies (University of California Press, 1995) 16; Lynda Nead, Victorian Babylon: People, Streets and Images in Nineteenth-Century London (Yale University Press, 2000) p.98. Further, see Chris Otter, The Victorian Eye: A Political History of Light and Vision in Britain, 1800-1910 (University of Chicago Press, 2008).

[4] Constance Classen, ‘Introduction: The Transformation of Perception‘ in Constance Classen (ed.), A Cultural History of the Senses in the Age of Empire (London: Bloomsbury, 2014) 8-10.

[5] ‘Jubilee of Gas Lighting in Bristol’, Bristol Mercury, 7 Sept 1861, p.4.

[6] ‘Exposition of the Oil Gas Scheme’, Bristol Mirror, 3 March 1823, p.3.

[7] ‘Exposition of the Oil Gas Scheme’, Bristol Mirror, 3 March 1823, p.3.