University of Bristol historian Lena Ferriday concludes BDFI’s ‘History of the Sheds’ project with a summary of the living histories collected to inform its place the former industrial community of The Dings and St Philips. Alongside artist Ellie Shipman, Lena interviewed former local residents and employees of the Bristol Gas Company to uncover how it felt to live and work among a transformational industry for Bristol.

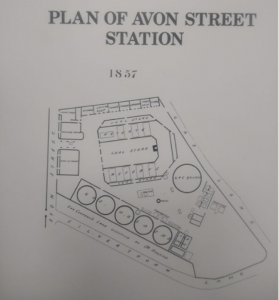

In June 2022, the BDFI became the first inhabitants of the new Temple Quarter Campus when they moved into their new building at 65 Avon Street. As part of this relocation, they were keen to investigate the histories of this site which once housed Bristol’s gasworks, in order to draw connections between the socio-technical pasts, presents and futures of the space. Following extensive archival research conducted by Dr James Watts, the two of us wrote a report which revealed the gasworks and gas industry’s important influences on Bristol in social, economic, environmental and technological terms. But we also identified that what was missing from the written record were the voices of those who lived and worked in the vicinity of this site, whose memories are obscured in the archives. As such, the project became a more participatory one.

After publicising a call for contributions, I conducted a set of oral history interviews with local residents who were all differently connected to the site of the gasworks. Concurrently, we commissioned illustrator and artist Ellie Shipman to work alongside us to produce an artistic response to the histories we were continuing to uncover and write. Ellie also engaged with members of the public through interviews and memory café chats – with the help of local historian and co-founder of the Barton Hill History Group Garry Atterton.[1] Across these conversations – both structured and less formal – themes highlighted in the previous report were brought out in animated, lively ways.[2] But people’s tangible memories of the site also took the history in new ways, sometimes with narratives that competed with the stories told by archival material.

Environment

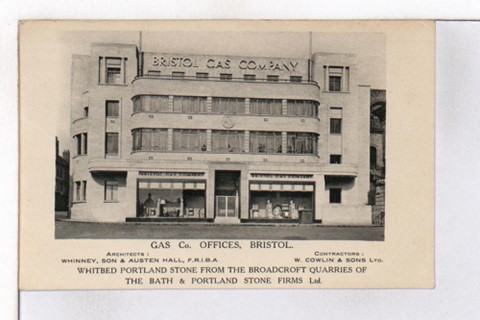

Our original report had identified that the gasworks opened in 1821 and was frequently renovated until its decommissioning in 1970. In an interview with Geraldine Stone, who lived in East Bristol in the 1960s, she relayed that ‘I just remember the gasworks as big grey stone buildings that almost frightened you … cause they were again grey and dark’. This perspective of the building from the outside – as perhaps relational to the way in which the majority of Bristol’s inhabitants will experience the refurbished BDFI building – demonstrated the emotional power of the site on the memories of those who lived nearby. But they also showed the gasworks’ relationship to the other buildings in this industrial area. From the nineteenth to mid-twentieth centuries, this area of Bristol was fiercely industrial.

Neighbouring the gasworks were an ironworks, a vitriol works, a lead works, a paint works, a marble factory, a railway engine works, the railway and Temple Meads station, a timber yard and a dye factory. As Garry explained, ‘The Feeder Canal was sort of a good thing and a bad thing, in some respects. It was a good thing because it was an artery that spread the heart of Bristol out to other parts of the city … But because of the flat land that was available, it was brilliant for industry… What you saw in that time was a massive concentration of heavy industry that had not been seen in the city.’ Geraldine recalled that the area was ‘always dark, you know. But it was mostly the smells in everything that was going on, and because it was the centre of St Philips and The Dings, it was something that you lived with every day, because you didn’t have cars, you would walk everywhere.’ For Geraldine, living as a pedestrian in this area led to a particular form of sensory engagement with the industrial space, and also led to an understanding of Avon Street a transitional place: ‘To me Avon Street was a way of getting through to anywhere. It was a throughway.’

For Geraldine this dark, smelly area also produced a particular atmosphere in the area: ‘in those days when you had the trains and smoke, well in our days as a small child everything was smog. It was just smog. It used to come down really low and you couldn’t see…’ In the report we attested to the concern for the environmental impact of gas that was demonstrated nationally in the nineteenth century, and the moves within the Bristol Gas Company to reduce pollution.[3] In his interview with Ellie, Garry corroborated this, writing that ‘You had this massive concentration there, which potentially was all going in the Feeder. All the pollutants.’ The report also attested to the company’s attempts to ensure this pollution did not cause medical concerns. Members of the Barton Hill Group recalled that those who worked in the area struggled with chest and lung issues – ‘coming home with really heavy coughs’ – although here Lysaghts steel works and the cotton factory were more frequently listed as embodied polluters than the gasworks.

Society

In the report we noted that this pollution made the gasworks an uncomfortable and challenging workplace. Richard Nicholls, whose father worked as a foreman at the site from 1944, noted that this physical atmosphere also had a social impact on the employees:

“It was unusual in those days for engineers to be able to talk about their marriage, their sex life or whatever. Because they were in what were dangerous conditions, you know, really hot there, the hot coals there and so on. So when they were in that condition they were very much a family of their own and looked after each other…”

Here, Richard attested to a community within the group of men working at the site that the archival records had shown to an extent, through evidence of an employee brass band and football team. Richard’s intergenerational memories bring this collegiality to life with stories. He noted that ‘it was very much a mick-taking humour’ between colleagues, recalling the instance in which ‘One of the guys had his shoes nailed down to the floor cause when they’d go to the building sites they’d change shoes, … and he had to go back in his muddy boots.’

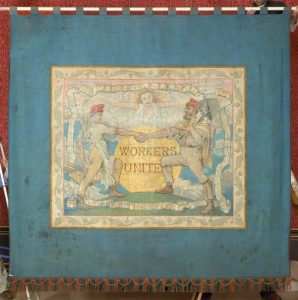

It was the dangerous conditions that Richard also linked to the success of trade unionism within the industry: ‘that’s why the strikes were so solid, because they were family, they relied on each other, they could talk to each other about anything. They could speak their mind as it was. Very hard men, very stuck together.’ In our initial report we identified Bristol gas workers’ strong involvement in the strikes of 1866, 1889 and 1920, the archives attesting to the outcomes of this action. But the internal mentalities of those striking were not documented, and Richard’s comments are enlightening here.

The successful 1889 strike saw a dispute over shift length, with workers petitioning for a move from 12 to 8-hour shifts. By the time Richard’s father was employed at Avon Street, shift patterns were fairly regular: ‘The normal one would be 8 till 5, 8 till 6, that sort of thing’. When engineers worked on call, however, they could be called out to emergency leaks across the city at any time. Richard noted that ‘it wasn’t a case of you said no. You went.’ The gas works were therefore closely connected to the insides of Bristolians’ homes in a way the archives had not accounted for, not only via the material substance of the gas but also those who monitored it. But it was not only engineers who brought the gasworks into the home. Members of the Barton Hill group recounted memories of company employees visiting to collect money from the gas meters, an exciting day as they would often get money back. Richard remembered ways in which people would also get around this system in certain ways: ‘there was a mechanism inside the meter where you could change the rate that you’d pay for your gas, and they used to get them to change it so that the money would go in … then when the meter reader came they’d make them a cup of tea, oh you’ve overpaid us this much, so they’d give them a refund out of the money that was in the thing’. Others would put coin-shaped objects into the meter to get themselves through the week until they confessed on collection day.

Technology

This connection into urban homes came with its difficulties. Archival records attested to concerns about the dangers of gas circulating from its introduction in the early nineteenth century, and numerous gas explosions were reported in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Members of the Barton Hill History Group similarly remembered a gas explosion that flattened two houses on Lincoln Street in the early 1950s.

Difficulties with gas not only arose from fears regarding its danger – from the 1890s acknowledgment of the efficiency and stability of electric light in industrial settings (beginning with the Wills Tobacco factory) posed a challenge to the Bristol gasworks. Yet gaslighting remained popular for longer than expected, and many of the participants in our project had strong recollections of it. When working as a gas engineer in Bristol, Richard recounted being called out to a house that still had no electricity in 1972: ‘She had gas lighting, gas cooking … So it’s amazing how long it was before some people had electrics.’ Richard noted being concerned about the hazards of the lighting here however: ‘the gas lights had little chains on that you could pull down to turn on and … She wanted me to lower it. She had big frizzy hair. And I thought, well if I lower that down, it’s going to be so near her hair – I could just see it going whoosh!’, he laughed.

The gasworks also contributed to energy in the home via other materials than gas. Members of the Barton Hill group recalled taking metal prams down to the gasworks to collect bags of coke for the fire – coke being a purified substance created in the production of coal gas. The elongated transition to electricity also shaped memories of gas itself, particularly given that gas is still used in many homes but now for cooking and central heating, rather than lighting. One member of the Barton Hill Group referred to cooking gas as ‘normal gas’, in comparison to the historic gas substance used to fuel lights. Yet in her interview Geraldine spoke of ‘the gas lamp posts being lit by somebody, by a man coming with a stick.’ Here too, however, her memories become sticky: ‘I don’t know if I imagined it – I didn’t and I know I didn’t …. so I think is that my vision or did I see it? But I’m sure I did …. Cause it used to shine all the time into my bedroom.’ Although she described the memory in detail, the chasm between gaslight technology and contemporary lighting innovations has worked to obscure her own visual childhood memories.

Conclusion

In the first report published on our findings about the site of Bristol gasworks, we concluded that ‘The tension between the benefit and harm brought by the introduction of gas to the city … is what characterises the history of this site.’ Predominantly the living histories we have collected have also pointed towards contested and competing narratives operating within the history of the gasworks. Gas was hazardous to the local landscape and residents’ bodies in the short term, with explosions destroying buildings and injuring inhabitants, and on a longer time scale, polluting the waterways and atmosphere which in turn brought on lung and chest issues for those immersed in them. Yet it also played a formative role in people’s fond memories of the area.

Given the BDFI’s emphasis on ensuring that the production of digital technology is inclusive and sustainable for the societies it affects, that the findings of these oral histories attest to the environmental, social and technological dimensions of the site is of great importance. Acknowledging via archival material that the former proprietors of the site also worked to reduce the environmental impact of innovative gas production, and that their employees campaigned for workplace equality provides a source of inspiration for the ways in with the Institute now inhabit this site in the present and into the future. The findings of the living and community histories that this new report has attested to, however, stretch beyond the site itself, and reaffirm the wider range of forms engagement with the gasworks site took. The gasworks had strong connections both to the wider industrial area of St Philips and to homes across the city, and in a similar way through this project the BDFI has maintained this connection between the sites and local communities through the sharing of memories. In addition, this project has amplified lived experience and as such demonstrated the importance of considering the individuals who are impacted by innovation in diverse ways.

Acknowledgements

The quotes in this piece are excerpted from recordings by Lena Ferriday with participants Geraldine Stone and Richard Nicholls, and Ellie Shipman with Garry Atterton, Pete Insole, and members of the Barton Hill History Group, Bern and Gill. We are very grateful to all those involved for sharing their time and memories with us, which have brought to life this historic site.

About the author

Lena is a PhD researcher in the Department of History here at Bristol, with an interest in modern histories of bodies, the environment and everyday experience. Her research has previously explored other areas of Bristol – including the city’s transport networks, tourism, green spaces and the history of the University – and she is currently writing a history of embodiment in nineteenth century Cornwall.

Lena is a PhD researcher in the Department of History here at Bristol, with an interest in modern histories of bodies, the environment and everyday experience. Her research has previously explored other areas of Bristol – including the city’s transport networks, tourism, green spaces and the history of the University – and she is currently writing a history of embodiment in nineteenth century Cornwall.

Notes

[1] A memory café is a community group that gathers people with shared memories (often of a place or event) to meet and discuss. The Barton Hill History Group run a monthly memory café, the August instalment of which Ellie joined.

[2] An edited audio piece including excerpts from these recordings was created by Ellie Shipman, and can be listened to here.

[3]This is also expanded in another blog post I have written to complement the project, considering the ways in which the senses profoundly shaped the urban production of gas.

Convolution increases the challenge, in that rather than just igniting an encounter between maths and poetry, we are trying generate opportunities for the two fields to influence and mutually modify each other, creating something new in the process. For our second edition, we spent a lot of time reflecting on the ways we have seen mathematics influencing poetry, particularly by creating new forms and possibilities for poetic production. This direction of influence is pretty well established in our experiments, and builds on earlier work we did in collaboration with the

Convolution increases the challenge, in that rather than just igniting an encounter between maths and poetry, we are trying generate opportunities for the two fields to influence and mutually modify each other, creating something new in the process. For our second edition, we spent a lot of time reflecting on the ways we have seen mathematics influencing poetry, particularly by creating new forms and possibilities for poetic production. This direction of influence is pretty well established in our experiments, and builds on earlier work we did in collaboration with the

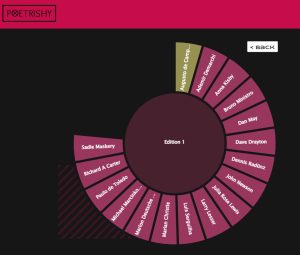

Our designers, Russell Britton (web designer) and Johanna Darque (print designer and co-editor), did such a fantastic job of bringing together a huge diversity of contributions, and in navigating the affordances and needs of digital versus print publishing. You should definitely check out both versions,

Our designers, Russell Britton (web designer) and Johanna Darque (print designer and co-editor), did such a fantastic job of bringing together a huge diversity of contributions, and in navigating the affordances and needs of digital versus print publishing. You should definitely check out both versions,

These community-led initiatives allow for open and speculative conversations that generate knowledge (in opposition to traditional forms of XAI), moving from individual to community understandings of what constitutes AI, and shifting the focus of attention from the past and present to possible futures. The next steps of our project involve supporting community engagements by the community groups to reach into their local areas and produce new XAI approaches that empower and give agency to different data publics.

These community-led initiatives allow for open and speculative conversations that generate knowledge (in opposition to traditional forms of XAI), moving from individual to community understandings of what constitutes AI, and shifting the focus of attention from the past and present to possible futures. The next steps of our project involve supporting community engagements by the community groups to reach into their local areas and produce new XAI approaches that empower and give agency to different data publics. This project allows us to collectively explore ways to explain machine learning models beyond providing technical accounts of data and complying with legal requirements. It shifts the perception on what makes AI explainable with an enhanced understanding of how machine learning is shaping the organisation. Moreover, it has given us, both the research team and LV= GI practitioners, space to form deep connections, share co-working spaces, and expand our partnership even further.

This project allows us to collectively explore ways to explain machine learning models beyond providing technical accounts of data and complying with legal requirements. It shifts the perception on what makes AI explainable with an enhanced understanding of how machine learning is shaping the organisation. Moreover, it has given us, both the research team and LV= GI practitioners, space to form deep connections, share co-working spaces, and expand our partnership even further.